The Fabbrica Design 2022 residency on the theme of vegetal fibers will be for me the opportunity to conduct a research-action project combining extensive fieldwork and explorations around the material, as a continuation of my work, in order to make it resonate with the specificities of the Corsican island territory hosting this research.

![]()

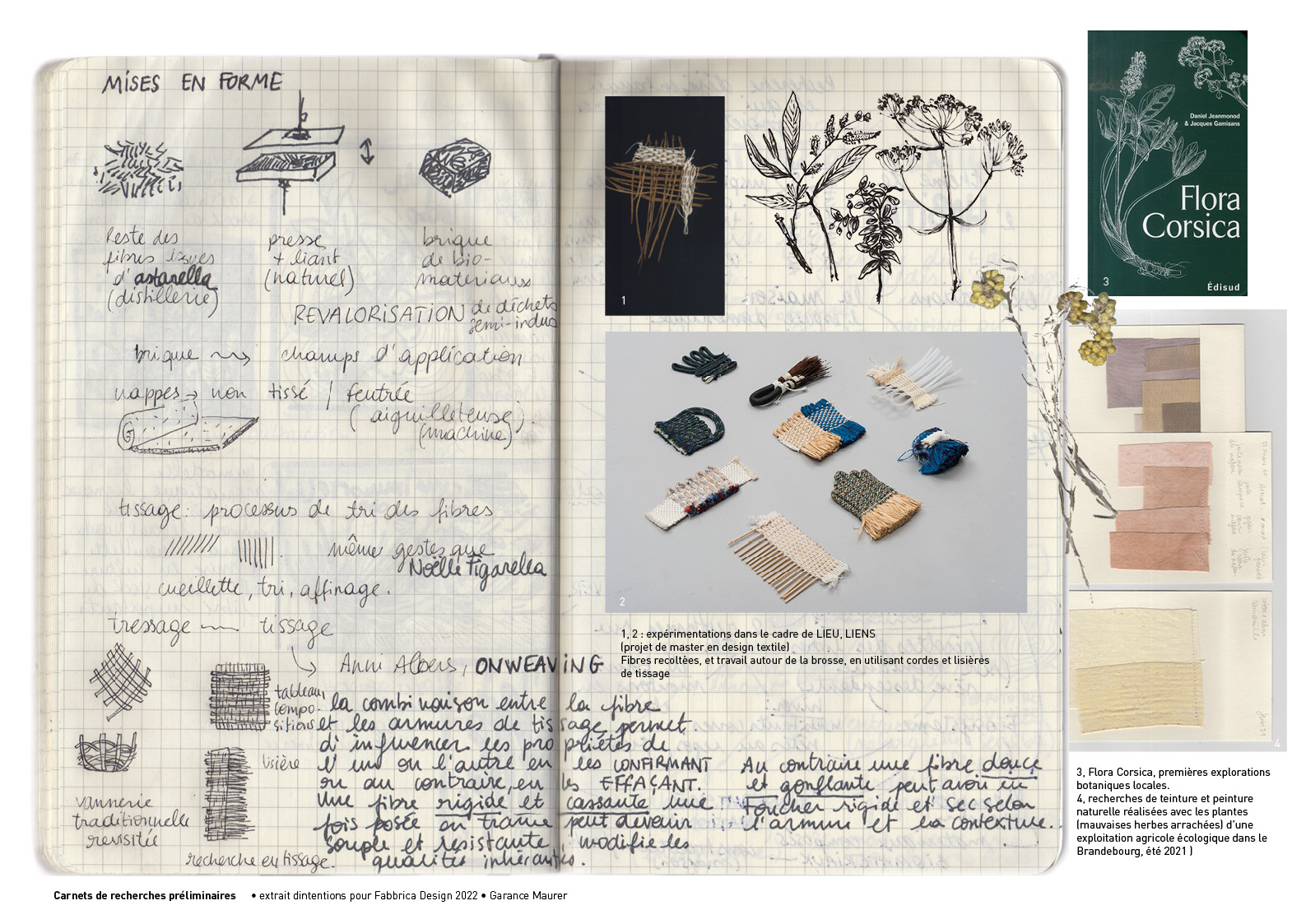

Setting up observation and creation protocols close to ethnographic design and anthropology; meeting the humans and non-humans of a territory; feeling and becoming this ecosystem; looking at and understanding the place that one discovers or rediscovers, are for me the foundations of any creative intervention. It is then in a second step that I will use all the creative tools acquired during my seven years of studying as in my professional and personal experiences to bring out a local and contemporary issue, to finally try to respond to it. The collaboration with local actors is one of the most enriching components of the work.

The theme of plant fibers intertwines my questions about the living and textile processes. This bound comes nourishing a research that I lead since several years, in which I consider the textile as a privileged tool for material and symbolic construction.

When questioning our ways of dwelling and what makes up our interior and exterior environments, the place of textiles appears to be central. Many aspects of our lives converge towards it: it comforts and protects us, dresses us and represents us. It can be considered as the first solution that humanity put in place to survive : weaving roofs, clothes or baskets even before making fire, cooking food or counting (see Gottfried Semper and Tim Ingold). Like an extension of the skin, textiles are an additional, and mobile, barrier to adapt to potentially hostile climatic events: as a thermal protection, shade or shelter from the rain for instance. Humans also adapt to the environment via textiles, as individuals or as a collective. Like a membrane that would mark the difference between interior and exterior spaces, like a skin would contain a body: a fabric that is stretched or laid down can mark the limits between a private piece of land, a home and a shared, public space. Closely linked to the question of language, weaving is also for me a tool for building meaning and participates in the writing of intimate and common history: the words text and textile are etymologically linked, in Latin for example, where the x of textus embodies the interweaving of fibers between the warp and the weft. Thus, by going to meet those who harvest fibers, those who shape them, braid them and weave them, we are telling a subtext generally relayed to the sphere of domestic work.

In terms of textile construction, as Anni Albers explains in her text On Weaving, the combination of the fiber and the weaving bindings can influence the properties of one or the other by confirming or erasing them. In that sens, a stiff and brittle fiber, once laid in weft, can become soft and resistant, thus modifying its inherent qualities. On the contrary, a soft and swelling fiber, worked in canvas with a high context will have a more rigid and dry aspect or touch. The numerous stages of transformation bring the possibility to go in one direction or the other, thus multiplying the field of applications. Through this first aspect of weaving, I see textiles as a particularly intelligent and inclusive response, allowing the construction of a material that adapts to the reliefs of life. Using a simple binary system (which can become more complex), allows us to embraces the difference of each element to form a resilient whole. Also, compared to other types of shaping techniques, the textile construction is soft. Beyond the touch of a fabric, its softness is close to a sensitive posture to the environment, social and ecological. Used under this prism, it becomes a means of resistance. Indeed, to shape wood we need to cut it, we carve in the material (with sharp objects, creating a significant part of residues). To work with metal, ceramique or glass, we have to heat the material, thus implementing very energy-consuming processes and operating brutal changes of forms. Textile creation, on the other hand, only requires the ordering of already existing elements, without making any major change of state. Through order, tension and patience we create flexible and adaptable surfaces. It is particularly this posture of intelligence of "doing with what is there" and bringing this care of arrangement and tension -or attention- that I wish to defend in my projects.

Concerning basketry, the central technique for this residency on vegetale fibers, the reading of the text The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction by Ursula K. Le Guin, 1986, an American feminist author, will be my starting point, joining my research on the origins of weaving.

" ’The first cultural device was probably a

recipient .... Many theorizers feel that the

earliest cultural inventions must have been

a container to hold gathered products and

some kind of sling or net carrier.’

So says Elizabeth Fisher in Women's

Creation (McGraw-Hill, 1975). But no, this cannot be.

Where is that wonderful, big, long, hard thing, a bone, I

believe, that the Ape Man first bashed somebody with in

the movie and then, grunting with ecstasy at having

achieved the first proper murder, flung up into the sky,

and whirling there it became a space ship thrusting its

way into the cosmos to fertilize it and produce at the end

of the movie a lovely fetus, a boy of course, drifting

around the Milky Way without (oddly enough) any

womb, any matrix at all? I don't know. I don't even care.

I'm not telling that story. We've heard it, we've all heard

all about all the sticks spears and swords, the things to

bash and poke and hit with, the long, hard things, but we

have not heard about the thing to put things in, the

container for the thing contained. That is a new story.

That is news."

As a result, in my explorations in the Corsican territory, focused in understanding the contrasted temporalities of the island ecosystem; the management of the island's biodiversity as a natural heritage and as a local resource; the architectural, artisanal, cultural and folkloric traditions; I will also follow the paths of this transversal research. The realizations will most certainly meet the notions of care : care of the body, of the house, of the environment, of the spirit of a place and the memory. They will probably take the form of objects vectors of symbolics and activators of rituals. Our senses, activated by the vegetation and climate of the island, will be honored. The gestures of the shaping techniques will merge with the functions of uses. The materials will be diverse and generous as I will work with the whole plants, semi-products or waste. They will always be local. The collaborations and hybridizations will be numerous, between naturale, flessibile/rigidu, cunfruntà and innuvà, central themes of the Fabbrica Design spirit. The experiments and the meetings will be put to the service of a local material and immaterial heritage through ethical and innovative means of production.

Edition #8 of Fabbrica Design, supported by the Foundation

of the University of Corsica,

in partnership with Natalina Figarella (basket maker, L'Astratella (essential oil distillery) and the Conservatoire Botanique National de Corse.

Ongoing research

Harvest